For Naga ethnic groups inhabiting the Naga Hills in the Indo-Myanmar

trans-borders, the road to peace and prosperity lies in forging a

common political Naga identity. There are several models the world over,

both old and new, that could serve as examples on a comparable scale

for political solidarity amongst geographically neighbouring people with

similar but subtly varied cultures. Most of these cultures also are in

disadvantageous juxtaposition due to external impositions of State

administrations and territorial demarcations, with serious implications

for the traditional homeland setup of these ethnic groups. In the past

the formation of the Six Nations in North America, more recently the

multinational struggle of the Kurds in the Middle East, nearer to home

the evolution of the modern nation of Bhutan and currently the campaign

for autonomy of Kachin neighbours of the Nagas are good instances of

affiliated ethnic groups and tribal clans seeking common ground for

collective political goals. The Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO)

of the Kachins has a civilian-run extra-legal bureaucracy providing

public services in Kachin State. Bhutan has several ethnic groups with

one dominant group-controlled absolute monarchy. The country has

recently made a successful transition from monarchy to a constitutional

democracy. The Kurds of Kurdistan are currently a nation in the making

in a trans-border conflict zone contiguous with Armenia, Iran, Iraq,

Syria and Turkey. In early American history, the Six Nations, also

called the

Iroquois, was a confederacy of different Native

American ethnic groups. Today, this powerful super group has unified

independent governance, and lives both in the United States and Canada.

As a historical illustration, in contrast to the success of the

Iroquois

was the Great Sioux Nation made up of several ethnic groups whose

traditional homeland once spanned across thousands of square kilometres

in the Great Plains of the U.S. and Canada. The Sioux being formidable

warriors, but divided along group loyalties, lost a major chunk of their

territories to the invading U.S. military, including the Black Hills,

which are sacred grounds since ancient times for the Sioux and remains

lost to them even today. The once proud peoples have been reduced to

living in scattered reservations in the land of their ancestors. In

2007, a group of Sioux travelled to Washington DC to reassert their

independence and sovereignty.

Naga Identity: Ideal versus Reality

The Naga Hoho, while being the apex civil society body of the Nagas

striving for a unified Naga identity, has been fighting a losing battle

bringing reconciliation to the several factions of Naga militias divided

along tribal lines or factional loyalties, which override ethnicity.

Naga tribes in their ancestral homeland face the divisive international

boundary between India and Myanmar as well as national administrative

boundaries in both countries. However, much more than man-made lines on

maps, the major challenge towards building a cohesive political unit is a

fragmented identity engaged in internecine strife with bloodied

consequences, which is in opposition to the larger Naga identity. As an

illustration, the Zeliangrong United Front (ZUF) is an armed ethnic

militia of the Zeliangrong Naga group consisting of the smaller Zeme,

Liangmei and the Rongmei ethnic groups. Zeliangrong groups are spread

over contiguous territories in Nagaland, Assam and Manipur States of

India. The Zeliangrong territory is also the domain of other Naga

faction rivals of the ZUF fighting for the Naga cause. There have been

several incidents of encounters between these competing Naga militias

vying to dominate the same geographical space inhabited by the

Zeliangrong people, especially between the ZUF and National Socialist

Council of Nagaland-Isak- Muivah faction [NSCN (I-M)].

Figure 1 - Major Naga Ethnic Groups' Areas

©

© Namrata Goswami

(Click here for a higher resolution image)

On the other end of the Naga identity spectrum is the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-

Khaplang faction NSCN (K) headed by S. S. Khaplang, who is a

Heimi Naga. The

Heimi

ethnic group belongs to the larger Tangsang Naga group including the

Pangmi, Khaklak and Tangan ethnic groups spread over contiguous

territories in Sagaing and Kachin States of Myanmar. In India, the

Tangsang group consists of the Tangsa, Muklom and Tutsa in Arunachal

Pradesh. The NSCN (K), with its headquarters in Myanmar, signed a

ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar government in 2012. This faction

holds sway over Nanyun and Lahe Townships in the Naga Self-Administered

Zone, with a liaison office at Khampti town in Sagaing Region of

Myanmar.

The Indian Government too has a ceasefire agreement

with the NSCN (K) since 2001, which has expanded its presence in Naga

inhabited areas of India. Traditionally the NSCN (K) has been challenged

in Naga inhabited areas of India by the NSCN (I-M). There have been

numerous deadly clashes between these two NSCN factions in a fierce feud

to dominate maximum Naga inhabited territory. As a few illustrations, a

significant development starting in the early 2000s was the advent of

NSCN (I-M) cadres into Arunachal Pradesh, originally the NSCN (K)’s

backyard, turning the peaceful districts of Changlang, Tirap and the

newly formed Longding into a battlefield. Both factions were fighting

for dominance in Naga inhabited areas of the State, when in 2009 the

NSCN (K) brought in their traditional ally, Myanmar’s heavily armed and

battle hardened Kachin Independence Army (KIA) to take on the NSCN

(I-M). The NSCN (K) also combined forces against the NSCN (I-M) with

non-Naga militants like the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) and

the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) of Manipur, both of whom

have camps in NSCN (K) active areas in Arunachal Pradesh and bordering

the Naga Self-Administered Zone, Myanmar. In 2006, the internecine feud

between the NSCN factions took an unprecedented turn when the NSCN (K)

issued ‘quit notices’ to all Tangkhuls in Nagaland, accusing that ethnic

group of ‘masterminding terrorism against the NSCN (meaning the

Khaplang faction) and innocent Nagas’.

1

Members of

the Tangkhul ethnic group from Manipur are exclusive cadres of NSCN

(I-M) and with this move the NSCN (K) was attempting to deny Naga

affiliation of the Tangkhuls.

Figure 2 - Areas of the operations of the NSCN factions

©

© Namrata Goswami

(Click here for a higher resolution image)

The biggest blow to the NSCN (K)’s pan Naga influence in India came

with the formation of the NSCN-Khole Kitovi (NSCN-KK) faction on June 7,

2011. The faction was formed by a dissenting group of cadres and their

leaders, Khole Konyak and Kitovi Zhimoni, from the NSCN (K). Khole

Konyak is from the Konyak ethnic group, the largest amongst the Nagas of

Nagaland State. An interesting fact is that the Konyaks are the

dominant group in contiguous Lahe Township, headquarters of the Naga

Self-Administered Zone in Myanmar and also inhabit Khampti Township of

Sagaing Division in Myanmar (See Figure I). Kitovi Zhimoni is a Sumi

Naga who are numerous in Nagaland. Since both the NSCN (K) and NSCN (KK)

occupy the same ethnic territories, there are bitter and deadly

shooting incidents/encounters between the two splinter factions for

military dominance. However, presently, the NSCN (KK) are focused on the

current boundaries of Nagaland with the goal of pushing out and

limiting the NSCN (K) to being a diminished Myanmar based outfit.

Figure 3 - NSCN (I-M)'s claimed Nagalim

©

© Namrata Goswami

(Click here for a higher resolution image)

NSCN (I-M)’s

Nagalim

i.e. the lofty goal of an independent ‘Greater Nagaland’ encompasses

large swathes of contiguous territory inhabited by both Naga and

non-Naga ethnic groups in India and Myanmar. In Myanmar, major chunks of

claimed areas have mixed Naga and other ethnic groups populations.

Tanai Township in Kachin State have several Naga villages along with the

Kachins. Even Khampti Township, which was earlier headquarters of the

‘Burma Naga Hills District,’ have a sizeable minority of Nagas living

with Bamar, Shans, Chinese and Indians. Other ‘Naga towns’ like

Homalin,

inhabited by fewer Nagas, are dominated by Bamar, Shans, Chin, Chinese

and Indians. The NSCN (I-M) has not been active in Myanmar to press

their claims of

Nagalim after a declared ‘unilateral ceasefire’ with the Myanmar government.

The

Nagalim

territorial claims in India include large strips of territory

peripheral to Naga inhabited areas, which have minuscule Naga

populations as in Assam’s Cachar, Nagaon, Golaghat, Jorhat, Dibrugarh

and Dhemaji districts. In Dima Hasao (formerly North Cachar Hills)

district, Nagas are a sizeable minority and a small minority in Karbi

Anglong district of Assam. Arunachal Pradesh’s Lohit, Anjaw, Dibang

Valley, Lower Dibang Valley and Upper Siang districts are inhabited by

ethnic groups such as the Adi, Mishmi, Zekhring, Khampti, Deori, Monpa,

Memba, Tai Ahom, Singpho, Chakma and Tibetans, with distinctive

identities bearing no affiliation to Naga ethnicity. The NSCN (I-M)

however, has been actively engaged in endeavours to expand its influence

to all Naga inhabited areas of India as well as mentoring other

non-Naga insurgencies of northeast India in a sort of titular ‘mother of

all insurgencies’ role.

The leaders of the NSCN (I-M) are

Thuingaleng Muivah who is a Tangkhul Naga and Isak Chishi Swu who is a

Sumi Naga, both from two of the larger Naga ethnic groups (see Figure

1). The Tangkhul Nagas form a large ethnic group in Manipur and

adjoining areas of Sagaing, Myanmar where they are called Somra Nagas.

Tangkhuls are the mainstay of the NSCN (I-M) and have taken the

faction’s fight to faraway operational zones like Arunachal Pradesh.

However certain major incidents illustrate the complex nature of the

ethnocentric support for the NSCN (I-M). In December 2013, the Sumi

Nagas of Nagaland threatened to evict the NSCN (I-M) from their lands.

The incident was triggered by the attempted rape and molestation of two

Sumi women and the grievous injuring of two Sumi men who were all

travelling to Zunheboto town. Their vehicle was allegedly waylaid by

four armed cadres of the NSCN (I-M) who perpetrated these actions. The

Sumis were further incensed by the failure of the NSCN (I-M) to later

hand over the culprits hiding inside the guarded designated camp,

instead attempting to compromise with the Sumi Hoho and even ‘pay off’

the victims to silence them.

In 2010 the NSCN (I-M)’s General

Secretary Th. Muivah made abortive attempts to visit his native village

in Manipur. These visits were stiffly opposed by the Manipur State

government as earlier ones had triggered violence in Naga inhabited

areas of the State. The NSCN (I-M)’s inclusion of Naga inhabited areas

of Manipur into

Nagalim evokes a deeply resentful response from the Meiteis for whom the issue is very sensitive.

The complexity of ethnic boundaries, as has been illustrated above,

forced divisions of ethnic communities inhabiting the border areas of

India and Myanmar by the imposition of an arbitrary international

boundary with little regard to local realities, and the framework of

policy-making that views ethnic groups as somehow pre-modern and in need

of development are the major existential and ideational challenges.

Inherent in this framework is a notion that somehow, the so called

mainstream culture and institutions are themselves not ethnically

slanted but universal.

2 In this scenario, policy making is

propelled by the ‘command culture of legitimacy’ that the public

administrators espouse, especially in dealing with minority communities,

which can backfire. Consequently, what is required, and which has not

been developed yet, is a deep seated understanding of the culture of

identity recognition and preservation. Most importantly, since

negotiations with armed groups in the Northeast are conducted in a

scenario of threat, it is important to understand this framework so that

there are no false expectations.

3

The challenge for

armed groups like the NSCN (I-M), NSCN (K), and NSCN (KK) is to meet

the claim of representation of a common Naga identity and community,

already run asunder by the territorial divisions brought about by a

modern state mechanism as well as by the internecine clan/tribe-based

fights that threaten the notion of common ethnic identity. Only time

will tell whether, like the Great

Iroquois, the Nagas can form a

common supra-national/transnational structure that provides a common

platform to their way of life and traditions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

References:

1For more, see “NSCN-K Quit Notice”, The Telegraph, January 30, 2007, at

http://www.telegraphindia.com/1070130/asp/frontpage/story_7324330.asp (Last accessed on June 14, 2014).

2For more on this, please see Wsevolod W. Isajiw, “Approaches to Ethnic Conflict Resolution: Paradigms and Principles”,

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24 (2000), pp. 105-124.

3Ibid

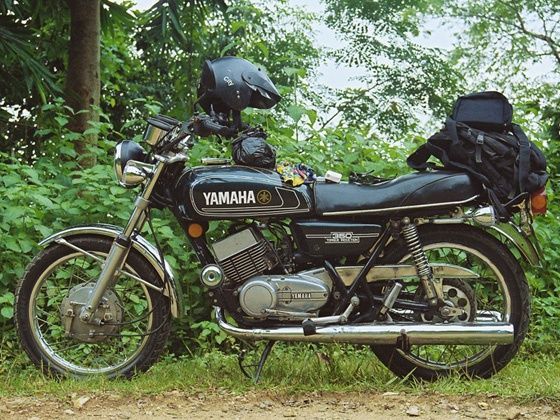

By Rahul Karmakar

By Rahul Karmakar

Sanamahhi

Motors proprietor W Kumar; Sales and Service Eastern Region manager for

Royal Enfield, RK Sachdeva; All Manipur Working Journalists’ Union

president Wangkhemcha Shyamjai, M Chitaranjan, G Prafullo and otheres

were in attendance.

Sanamahhi

Motors proprietor W Kumar; Sales and Service Eastern Region manager for

Royal Enfield, RK Sachdeva; All Manipur Working Journalists’ Union

president Wangkhemcha Shyamjai, M Chitaranjan, G Prafullo and otheres

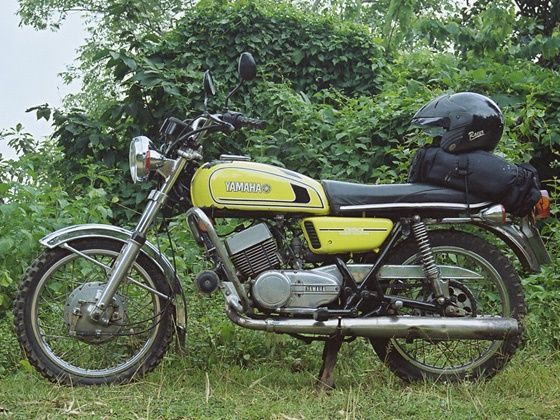

were in attendance.  Past

few years has seen the number of Royal Enfield riders in the state

grow. Royal Enfield has 307 dealerships pan India and is focusing on

North East, especially Manipur and Assam. Royal Riders Manipur has been

instrumental in getting riders together and organising activities here.

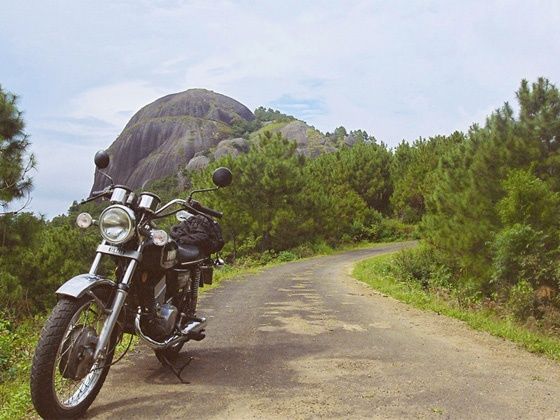

6th edition of North East Riders’ Meet (NERM) is scheduled for

5-7-Nov-2014 at South Loushing near Chingnungkhok, Lamlai, Imphal.

Past

few years has seen the number of Royal Enfield riders in the state

grow. Royal Enfield has 307 dealerships pan India and is focusing on

North East, especially Manipur and Assam. Royal Riders Manipur has been

instrumental in getting riders together and organising activities here.

6th edition of North East Riders’ Meet (NERM) is scheduled for

5-7-Nov-2014 at South Loushing near Chingnungkhok, Lamlai, Imphal. After

a long detour around Bangladesh, the riders reached Nagaland and

Manipur having first crossed Patna. The North eastern regions that feel

very different to the rest of India entailed a border crossing at

Nagaland guarded by heavy military presence, and foreigners have only

recently started entering these areas. The 10 armed women guards at the

border welcomed the riders.

After

a long detour around Bangladesh, the riders reached Nagaland and

Manipur having first crossed Patna. The North eastern regions that feel

very different to the rest of India entailed a border crossing at

Nagaland guarded by heavy military presence, and foreigners have only

recently started entering these areas. The 10 armed women guards at the

border welcomed the riders. With

breakdowns to be dealt with and no Enfield dealer in Imphal at the

time, the Aussies planned to contact Eddie, a member of the Royal

Enfield club, Royal Riders, but with no mobile network coverage, that

wasn’t to be. This is when Eddie pulled up on his Royal Enfield having

been riding around 2 states looking for them so he could ride with them.

The group left from Imphal after meeting more ‘Royal Riders’ before

heading to the Myanmar border.

With

breakdowns to be dealt with and no Enfield dealer in Imphal at the

time, the Aussies planned to contact Eddie, a member of the Royal

Enfield club, Royal Riders, but with no mobile network coverage, that

wasn’t to be. This is when Eddie pulled up on his Royal Enfield having

been riding around 2 states looking for them so he could ride with them.

The group left from Imphal after meeting more ‘Royal Riders’ before

heading to the Myanmar border.