The

Mizos of Tamu went out of their way, the group says, to ensure they

were not jailed and a formal case was not registered. It helped that the

elected representative of Tamu was, till his recent demise, a Mizo. The

local Mizos also bargained with the authorities to be allowed to feed

the detained group

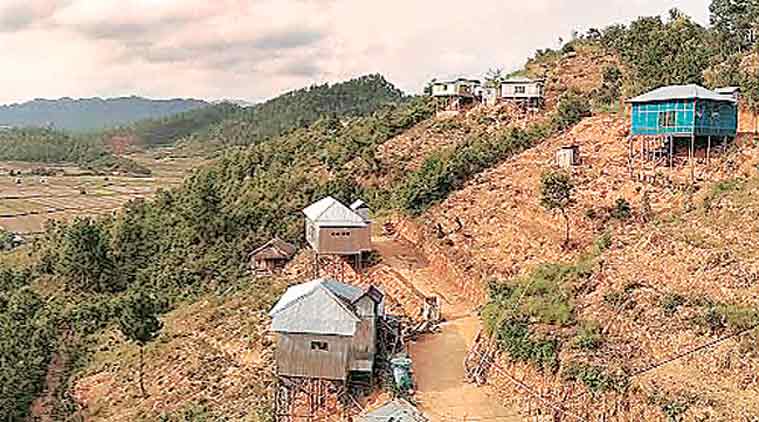

By the late 1980s, Tlangsam, a village of around 400 families, had come

to be known as the home of the religious sect ‘God’s Church’ that

feared a giant rock would roll down from the east and cause great

destruction (Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

UID number was that of the anti-Christ, they thought, and a war

and an unexplained darkness were coming. 19 people from Mizoram set off

on a 200-km trek across mountains to Myanmar, fuelled by this faith

rather than reason — and found love at the end. ADAM HALLIDAY retraces

the journey. Photographs by ADAM HALLIDAY

The district

A 3,185 sq km district with a population of around 1 lakh, Champhai has a

special place in Mizoram. It is said the history of Mizos starts from

Champhai and ends in Champhai. The town is also a fast developing venue

on the Indo-Myanmar border. The World Bank is currently financing the

building of a four-lane highway between the border village and Champhai

town.

A problem

A UIDAI drive is currently on in Champhai district. The 19 — members of

one extended family — belong to Tlangsam village of the district. An

official said members of ‘God’s Church’ sect of Tlangsam have largely

refused to be enrolled. An earlier round had been able to enroll just

over 38% of the district’s population and left out as many as 30

villages.

The trek

The Chin Hills of Myanmar, which the group wandered through, is an area

of ridges and deep river gorges similar to the hills of Mizoram or

Nagaland, only higher in elevation at between 2,000 and 3,000 metres

above sea level. Much of the region is thickly forested. Any kind of

road winds around these ridges. The 19 largely stayed off roads.

They left after day had given way to night, a small band of 19 men,

women and children looking east for refuge, from what they feared was an

impending doom.

Maduhlaia plays with Rammawii’s children (Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

They knew not what cloak doom would don or when it would arrive, but

the scanning of eyes for the Aadhaar scheme, they apprehended, was the

start. So they fled. Urgently. Secretly. In silence. Convinced their

destination would be revealed to them.

It was on March 15 that they left their village Tlangsam, trekking

and taking lifts over dense forests and mountains to cover, as the

crowflies, 200 km. It was on June 3 that they were returned home —

escorted by Myanmarese authorities.

Last week, this was the Myanmar story you didn’t hear about.

R L Hmachhuana, who is in his early 50s, was once part of the same

religious sect as the 19 in Tlangsam, a village that borders Myanmar. A

decade ago, he parted ways.

But while mainstream Church organisations in Mizoram have been saying

for years that the UID (the Unique Identification Authority of India

scheme) is not something to be feared, Hmachhuana isn’t surprised his

children and sister, their families and the others left like they did.

“In all of history, there has never been an identification project

for citizens that is linked with the power to buy and sell. UID is the

only one where your entitlements like rations and everything else are

linked to your number, just like the prophecy says of the anti-Christ’s

number,” he says.

Two of the children who went on the trek back home (Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

Two of the children who went on the trek back home (Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

“Some people argue that the Bible says the number will be on the

forehead, but the original Greek word means the upper portion of a human

face,” Hmachhuana adds, referring to the iris scan under UID. “That

includes the eyes.”

Hmachhuana’s sister Lawmzuali lives with her son in a house about 10

minutes away on foot, beside the main road that enters Tlangsam.

“We felt a calling in our hearts that we must flee. We feared the coming

of the darkness and the foretold troubles, and we left. It was not

particularly the UID, but a combination of all the signs of the end of

days,” she says.

The group included her husband, a 70-year-old man who had suffered a

stroke and who sometimes could not recognise family members, as well as

Hmachhuana’s daughter Rammawii with her three-year-old son, his sons

with their families including three children, a close family friend and

one pregnant woman.

They carried a change of clothes and food that was only enough to tide them over a couple of days.

At the head of the group was Lawmzuali, 50, who was entrusted with their entire savings of Rs 3,000.

In the beginning was Lalzawna. An erstwhile member of the Mizo

National Front, he moved with the front into East Pakistan in the early

years, and then to Myanmar’s Arakan region. In 1971, he claimed to have

“received” a message that said, “You will take part in a boat race, but

your boat will be different from the boats that others row.”

“We felt a calling in our hearts that we must flee. We feared the

coming of the foretold troubles,” says Lawmzuali. The 50-year-old led

the group and was entrusted with their entire savings of Rs 3,000

(Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

“We felt a calling in our hearts that we must flee. We feared the

coming of the foretold troubles,” says Lawmzuali. The 50-year-old led

the group and was entrusted with their entire savings of Rs 3,000

(Source: Express photo by Adam Halliday)

Eight years later, he began preaching a message of “cleansing the

flesh” in the insurgent camps. He returned to Mizoram soon after and

began travelling to spread his beliefs.

By 1984, he had moved with followers into Tlangsam and established

the ‘God’s Church’ sect. Some say Lalzawna’s followers numbered more

than 400 families and swamped the 50-odd families who made up the

original residents.

Soon Tlangsam came to be known locally as the home of the religious

sect that feared a giant rock would roll down from the east and cause

great destruction.

Hmachhuana again has an explanation. He had left his hometown Kolasib

near Assam to join the ‘God’s Church’ but abandoned it a decade ago

with his kin apparently due to “administrative problems”.

Hmachhuana, who makes a living as a carpenter and farmer and who

occasionally works at a saw mill in his yard, says he and his kin still

continue to believe they are the descendants of Ephraim, the patriarch

of the 10th tribe of Israel.

They also believe in the likelihood of a fierce war between the

armies of the east and west. Sitting in his tin-roofed wooden house,

Hmachhuana interprets the same as a war between the armies of China and

India, with Mizoram emerging as an independent country.

They see as well the coming of an unexplained “darkness” that would

destroy and create a new land, and UID as the number of the Biblical

anti-Christ that all “doomed humans” would sport either on their

forehead or right wrists.

The group of 19 headed for the Tiau river first when they left home

around 7 pm on March 15. The river, which in some places is no more than

a wide stream, serves as the international border with Myanmar, with no

fencing along it. When they got tired, they rested in the wilderness

near Khawzim, a border village.

The next morning, they say, they just waded across the Tiau into

Myanmar. And then walked further in to Tuidil village. When night fell,

they slept on the village’s outskirts, in a small abandoned hut.

Hmachhuana, whose children, grandkids made the trek, is clear the Bible

links eyes to anti-Christ’s number (Source: Express photo by Adam

Halliday)

Hmachhuana, whose children, grandkids made the trek, is clear the Bible

links eyes to anti-Christ’s number (Source: Express photo by Adam

Halliday)

It had been just two days, but their food supply was already running

out. Worried for the first time, they also realised the money on them

might prove inadequate. Hmachhuana’s dog, a large mongrel, had followed

the group from Tlangsam, refusing to be shooed away. At Tuidil, they

sold it for the equivalent of 2,000 Indian rupees.

By then Lawmzuali’s husband Zonghinglova, the oldest in the group,

had begun showing signs of weariness. When he fell ill, the young men

took turns carrying him on their backs. Lawmzuali remembers he resisted

this forcefully.

Zonghinglova had initially been sprightly, “the one most excited”

about the journey, she adds. “After a few days, he started feeling weak.

But he would keep saying he felt weaker when anyone carried him, and

insisted on walking.”

From Tuidil they kept going and reached Lentlang, proceeding onwards

to Laitui. Now approximately 22 km from the border, they said, they

reached a settlement of largely ethnic Mizos.

Lawmzuali admits they didn’t know where they were going, or had any

idea of the terrain they were crossing. The Chin Hills of Myanmar, where

the group would continue to wander about, is an area of ridges and deep

river gorges similar to the hills of Mizoram or Nagaland but higher in

elevation, between 2,000 and 3,000 metres above sea level.

Much of the region is thickly forested. Any kind of road winds around these ridges. The 19 rarely took one.

They pressed on, they say, in the belief that a supernatural presence “would show them the way”.

“Once we found ourselves at a fork in the road. Maduhlaia, who was

walking in the front, turned around and called to me, ‘Aunty, which way

are we supposed to go?’. So I told him, ‘You go wherever it seems

suitable’. I prayed, and after I was done praying, he had made up his

mind and said, ‘I’m going this way!’. And so we all went,” Lawmzuali

says.

Just before they reached Laitui in the Chin region, a band of

Myanmarese traders offered them a lift. The women, children and the

elderly got on. The eight young men kept walking, and the group reunited

at Run. They made a halt a little distance from the small town,

sleeping in the open.

As they resumed their journey the next day and headed towards Falam

township more than 40 km to the south, a truck came by and the driver

asked if they wanted a ride. “So we all got on. The driver asked us

where we were going, and I asked him in return which way he was going.

He said Tahan. So I said we’re also going to Tahan,” says Rammawii,

Hmachhuana’s daughter.

The group isn’t clear what route they took from Tahan, knowing little about the towns and villages they crossed on foot.

Around three days later, they found themselves close to the

international border where Manipur meets Myanmar. By now they had

ventured roughly 200 km from home. Some men — the group suspects they

may have been Manipuri or Naga rebels based in Myanmar — told them the

area was unsafe and took them to a village populated by the Thado

community. They believe it was called Usu, located anything between 10

and 15 km from Tamu town, the site of an official Indo-Myanmar border

crossing.

The story of the incredible journey was about to draw to a close.

The Mizos living in Tamu heard about a group from Mizoram being found

in the area, and went to get them. Soon the news spread, and Myanmar

police and immigration officials descended on Tamu to interrogate the 19

about out where they had come from and why.

The group was interrogated for an entire night, and then put under a

sort of house arrest. The 19 say the building seemed to be a school. By

then, a week had passed since they had fled Tlangsam.

The Mizos of Tamu went out of their way, the group says, to ensure

they were not jailed and a formal case was not registered. It helped

that the elected representative of Tamu was, till his recent demise, a

Mizo. The local Mizos also bargained with the authorities to be allowed

to feed the detained group.

However, there was a little trouble soon. “It was warm and the

children drank a lot of water. Us, too. We kept needing to relieve

ourselves, and we kept dispersing since we weren’t locked up. The guards

would tell us to stay put but we didn’t understand their language,”

giggles Rammawii.

The group was next put in two lock-ups, women and children in one,

men in the other, separated by a thin wall — a large holding area they

describe as about 50 ft by 20 ft each, also holding locals detained for

petty crimes. “Wide enough for the children to race around in, which

they did all the time,” says Rammawii.

On the afternoon of March 27, V L Chama Hnamte, president of the

Champhai district sub-headquarters of the Young Mizo Association, was

working on some child abuse related cases (he is also the chairman of

the district’s child protection committee) in Champhai town when he

received a call from an unfamiliar number. Champhai is sprawled on a

Mizoram hill just across a vast stretch of picturesque rice fields from

Tlangsam, and the Young Mizo Association is the state’s largest

community-based organisation.

The caller identified himself as Lalchatuana, leader of the Tamu Mizo

Thalai Pawl, a youth group of Tamu Mizos. As V L Chama listened with

increasing amazement, Lalchatuana told him about the group of Mizos from

Tlangsam who had found their way into Tamu and been detained by police

and immigration officials. Lalchatuana said they were trying to secure

their release and were making sure they received adequate food.

A large, energetic man, V L Chama immediately made his way to

Tlangsam and located Hmachhuana. The man with answers to most questions

told V L Chama he too had just come to know of his relatives being

detained in Myanmar, and had no idea what to do.

“He told me he was surprised the group had reached that far, that he

had assumed they would live in the forest along the international border

and come back after they had got over their fears,” says V L Chama.

Back at Tamu, the detention of the 19 continued. But the group’s memories of this time are of kindness, not hardship.

A police officer they named the “lord” because he had three stars on

his uniform and was evidently the highest-ranking officer there took

“very good care of us”, says Lawmzuali. “Every day he would come to the

cell and have the children examined for any kind of fever or illness. He

was especially mindful of the pregnant woman among us. He made sure she

got soup regularly, and got her examined very often.”

The Mizos of Tamu also kept up a steady stream of food supplies,

including rice, vegetables and, at least once a week, meat. The food was

prepared by the cook on orders from the “lord”.

The officer also made sure that enough water was kept in the cells,

though that led to a minor problem. As the days and nights were warm,

the 19 would often sneak out for a quick bath even at night. The officer

cut down their water supply after that, telling them through a

translator that the children would fall sick if they continued.

Some Mizos would visit them almost daily, buying them cigarettes from

nearby shops and passing these along with the help of guards. “Very

often the guards themselves would come to check on us,” says Rammawii.

She christened one of the guards, an officer with a star on his

uniform, “Boxer” because, as she recalls, he punched several of his

juniors after some inmates complained of verbal abuse.

Around the end of May, Lawmzuali’s husband Zonghinglova’s condition

got worse. A doctor diagnosed internal bleeding and he was kept in the

infirmary. His wife was allowed to tend to him.

On May 22 night, he passed away.

Lawmzuali says she won’t forget what followed. “I and my relatives,

the Tamu Mizos, the guards and even the ‘lord’ gathered around the body

and we put on gloves and masks and cleaned him up. I thought to myself,

‘He is my husband’, and I took off the gloves and touched him with my

bare hands. When the ‘lord’ saw that, he also took off his gloves and

helped me get him into new cloths for the burial.”

A CD containing video clips of the funeral and burial, given to the

group by the Tamu Mizos, shows the ceremony, with the group gathering

around the coffin and the guards and other officials looking distraught.

A convoy of 10-odd SUVs emblazoned with official symbols acted as the

funeral party as the coffin was transported to a Mizo cemetery some

distance away. Several officials can be seen in the funeral video.

Lawmzuali remembers one as the town’s administrative head and another as

the widow of Tahan legislator D Thangliana.

Lawmzuali recalls the officials telling her later, “As is your

community’s custom, you will one day wish to return and erect a

headstone on your husband’s grave. We will host you as family.”

V L Chama had kept in touch with Lalchatuana since that March 27

call. On May 23, he received another call from across the border. The

Tlangsam group had been released, he was told, and they would be coming

home soon.

On June 3 at 7 am, they arrived with an escort of Myanmar officials

and police and four Mizo leaders at the border crossing near Zokhawthar

village. V L Chama and his colleagues along with Champhai District

Deputy Commissioner H Lalengmawia were there to receive them.

“I am truly amazed the Mizos of Myanmar did everything they could to

get these people back home. An international border might separate us

but Mizos this side and that are bonded by the spirit of Tlawmngaihna,”

Lalengmawia said, receiving the group, referring to the traditional Mizo

code that puts the community above individuals.

Says V L Chama, “I have been asking myself how we would treat a group

of Myanmar nationals if they found themselves in the same situation…

What the Tamu Mizos told me more than once was how surprised they were

that the authorities did not even register a formal case, simply

detained (the 19) in a lock-up. They said that was unprecedented.”

By the evening of June 3, the group was back in Tlangsam.

Since then, the children have gone back to school, while the adults

are again working in their fields or at Hmachhuana’s small saw mill.

At her son’s home in Tlangsam, where she lives, Lawmzuali stares out the

window as she contemplates the events of the past three months.

After a silence of a few minutes, she says, “I buried my husband there.

Maybe we were heading for the place of his death and his grave all

along. He was the most excited among us about the journey. It must have

been God’s will. My heart is at peace.”

Paraolon (Manipur), Jun 17 : Speeding along the Asian Highway 1 (AH1) from

Manipur capital Imphal en route to the border town of Moreh, there is a

sense of peace. It kindles a hope that New Delhi’s ambitious plan to

connect North-East India to Southeast Asia through Manipur is really

taking flight.

Paraolon (Manipur), Jun 17 : Speeding along the Asian Highway 1 (AH1) from

Manipur capital Imphal en route to the border town of Moreh, there is a

sense of peace. It kindles a hope that New Delhi’s ambitious plan to

connect North-East India to Southeast Asia through Manipur is really

taking flight.

Kamjong village on the border; the Myanmarese provide teak, the

villagers give them ‘whatever they want’. (Source: Express photo by

Deepak Shijagurumayam)

Kamjong village on the border; the Myanmarese provide teak, the

villagers give them ‘whatever they want’. (Source: Express photo by

Deepak Shijagurumayam)

Hmachhuana, whose children, grandkids made the trek, is clear the Bible

links eyes to anti-Christ’s number (Source: Express photo by Adam

Halliday)

Hmachhuana, whose children, grandkids made the trek, is clear the Bible

links eyes to anti-Christ’s number (Source: Express photo by Adam

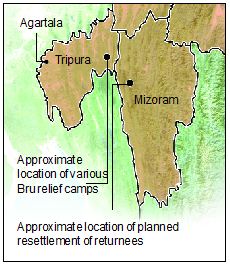

Halliday) Displaced Bru tribals return home to Mizoram from relief camps in

Tripura during the 2013 repatriation process.

Displaced Bru tribals return home to Mizoram from relief camps in

Tripura during the 2013 repatriation process.