From bootleggers to Church, vigilantes to youths, and government

to opposition, the battle lines are still drawn a week before

prohibition ends and liquor sales begin in the state. The longest lines,

however, are for permits to buy alcohol, finds Adam Halliday.

A middle-aged widow who has for years sold bootlegged rum at roughly

twice the original price sat at a friend’s grocery shop in an Aizawl

neighbourhood and contemplated if she should start a new line of

business.

With total prohibition ending and liquor outlets set to open March 2

across Mizoram, she reckoned, bootlegged alcohol would be profitable no

more, certainly not enough to feed her family, including a son and

daughter and an infant grandson.

Every Sunday for the past two months, she has been running a small

food stall on the pavement near her home. Two weeks ago, she also

started hawking second-hand clothes near it.

She still bootlegs, of course, and every hour or so young men on

motorcycles drive up to the main road near her basement dwelling to

quickly pick up a bottle or two — McDowell’s No.1 rum from Meghalaya for

Rs 500, that from Assam for Rs 400 (original price around Rs 150) — and

stash it in their bags before zooming off.

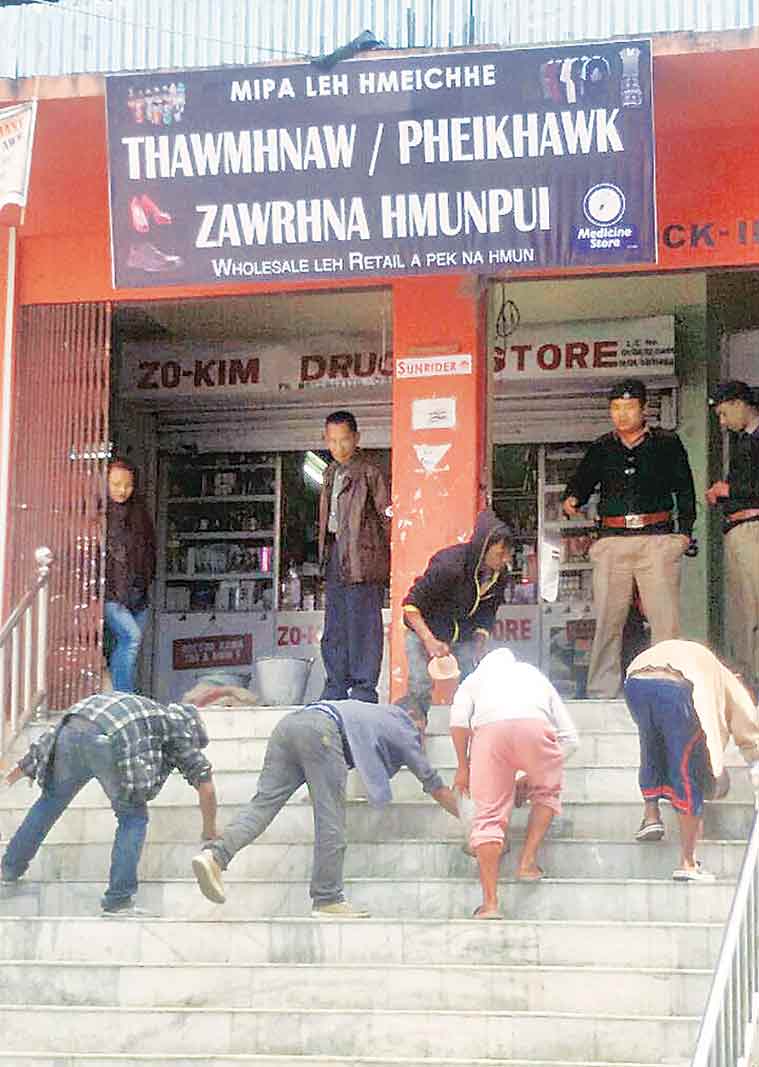

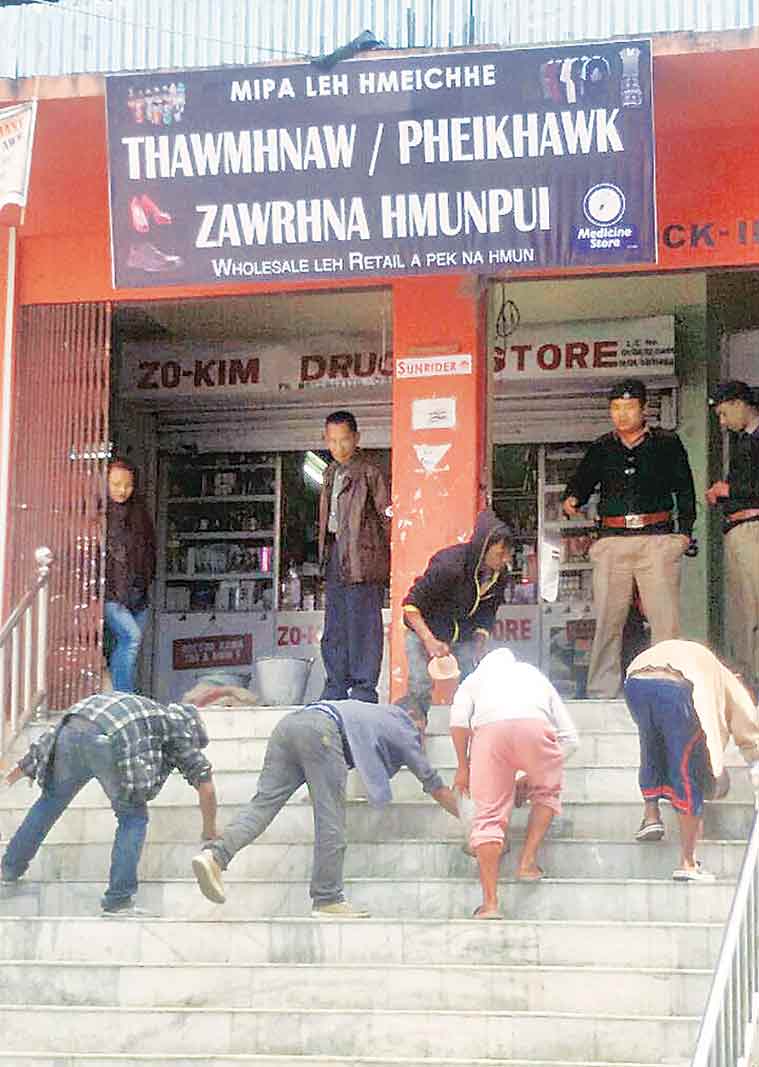

Those convicted under new law doing community service as punishment.

Those convicted under new law doing community service as punishment.

One night, as a group of four young men emerged from the steps

leading down to the dwelling, a man sitting at a nearby shop grinned,

“You guys willing to be frisked?”. The four smiled sheepishly, as one of

them put a finger to his lips and said “Shhh!”.

The end of two decades of prohibition may be something to say cheers

about for many in Mizoram, but not for the hundreds of bootleggers who

eked out a living from it, including many women.

Equally vocal about

their “dread” are thousands of parents, devoted Christians and community

leaders, who fear the open availability of alcohol will do more harm

than good.

Biaka Fanai, 18, is one of those not yet eligible to drink (the legal

drinking age has been set at 21), but he foresees what’s in store for

his peers. “For those who drink, it’s good because it’ll mean they will

get booze cheaper. But it’s definitely going to make people my age drink

heavily,” he warns.

Fanai explains why. “See, a lot of people my age are too proud to

drink indigenous fermented rice beer, and anyway you need to drive down

to the outskirts for that, and we usually don’t have vehicles of our

own. A bottle of rum or whiskey is available for Rs 500 or more at some

bootlegger’s place inside the city. But people my age are almost always

broke. So if five guys want to share a bottle, they have to pool in

about Rs 100 each. Once the outlets open, then the price will come to Rs

150 or Rs 200. So that’s just Rs 30 per head.”

What about the age limit? “Like that’s going to actually work,” he scoffs.

Upmarket Aijal Club that is the only one allowed to open a members-only

bar. No permits have been issued yet to bars, only wine-shops.

Upmarket Aijal Club that is the only one allowed to open a members-only

bar. No permits have been issued yet to bars, only wine-shops.

It was just before the 2013 state elections that Chief Minister Lal

Thanhawla spun the bottle. In a television talk show, he was asked

bluntly by the interviewer if his government, if voted back to power,

would lift prohibition. “We will review it keeping in mind what it has

done for society,” he replied.

In the months that followed, more and more government leaders began

talking about introducing a new law. Alcohol dominated conversations and

debates through much of Mizoram.

The government argued that studies had shown that prohibition had

failed completely and the number of people getting admitted in hospital

due to alcohol-related causes had increased because of large-scale

consumption of spurious liquor.

Come June 23, 2014, the Act was brought to the Assembly floor for a

debate. On July 10, people across the state stayed glued to their

television sets to watch live proceedings of one of the lengthiest

debates on a single issue in recent memory, lasting almost seven hours.

Revellers at Chapchar Kut (the traditional Mizo festival that falls in March) sneaking a few pegs near the venue in Aizawl.

Revellers at Chapchar Kut (the traditional Mizo festival that falls in March) sneaking a few pegs near the venue in Aizawl.

Finally, when a few minutes after 5 pm, the misleadingly titled

Mizoram Liquor (Prohibition and Control) Bill was passed, one policeman

on duty near the Assembly building shook hands with friends and said, “I

don’t drink much, I hardly drink at all. But finally we will be able to

get some good stuff when we do feel like it. It’s good.”

Soon the rules accompanying the new law were revealed. It would rely

heavily on permits, including for buying alcohol, and also involve fines

and jail terms for a number of offences. Liquor card holders would be

allowed no more than six bottles of strong liquor and 10 each of beer

and wine every month.

The punishment for breaking the law, varying from five days in jail

to five years, would be longest for offences such as drink driving,

causing ‘nuisance’ and drinking in public places — although magistrates

have been provided amnesty powers to commute both fines and offences to

community work.

Most importantly, the new law would empower citizens to arrest

offenders provided they were handed over to police or excise and

narcotics officials.

On January 15, the new law came into force, oddly more than one and a

half months before liquor was slated to be legally available in the

state and before any permit had been issued.

Since then, an estimated 40,000 people have applied for permits to have alcohol in the state.

The applicants admit the process is cumbersome, but add that they are

just happy to finally be allowed to drink legally. They are required to

submit a bank challan of Rs 520 each with their application forms, and

once they have braved the bank queues for it, submit the same after

lining up once more. The long wait for the liquor cards starts after

that, with their distribution yet to start. Even withdrawal of the form

invites a fee of Rs 20.

Doing the math, that’s roughly Rs 2 crore or more in government

coffers already, just from the issue of permits, not a bad start given

the government hopes to rake in Rs 30 crore every year from the

restricted sale of alcohol. That amount would roughly equal the Excise

Department’s entire earnings in fines from those who broke the law in

the two decades of prohibition.

In addition, bonded warehouses that will bring in alcohol from

outside and store it before it is sent to outlets have to pay Rs 1 lakh

each per year to the government. There will be two such warehouses to

begin with, and the contracts have gone to the family business of

Cabinet minister Zodintluanga and the firm of former Congress minister S

Hiato’s son.

The Cabinet minister incidentally had been the first one to support the new law during the Assembly debate.

The other major source of revenue for the government would be the

licence fee collected from vendors, of Rs 50,000 each per annum. Only

state PSUs (none of which has made profits in the recent past) and the

ex-servicemen’s association are being allowed to run outlets, apart from

the upmarket Aijal Club that has got permission to run a bar

exclusively for members.

Every brand has to pay a fee to be allowed to be sold in the state.

At least five liquor companies have already been approved to carry on

operations.

For example, Pernod Ricard will pay the government Rs 10,000 per

annum to sell its Seagram’s Royal Stag brand in Mizoram (where it is one

of the most bootlegged whiskey brands), while it will have to pay an

additional Rs 15,000 per year for the mono-carton each bottle comes in.

The Excise Commissionerate in Aizawl’s Tuikual locality is abuzz these

days. On the top floor, a team of officials is busy applying the

department’s official seal on thousands of freshly-printed,

fake-leather-bound liquor cards. These are about the size of passports,

containing pages where the date and number of bottles purchased are to

be marked.

An official hurries down to the office of a senior colleague and asks where more seals can be found.

The senior official, who is showing guests some sample bottles by

wine and whiskey makers who have applied for a licence to sell in

Mizoram, looks up as he replies, “First floor. There’s a box there.”The

junior official taps his heels in a salute and exits.

“We ordered 11 new seals just last week. They don’t last that long.

There are just too many cards to mark with them,” the senior official,

who doesn’t want to be named, quips as he flashes the business card of a

manager at Pernod Ricard and flips it over to show the embedded signs

of the various alcohol brands they manufacture and sell — a colourful

ensemble on a small piece of paper.

“You will be like Bethlehem although you are a small department. You

will be the source of much of the state’s finances,” Excise Minister R

Lalzirliana told a gathering of excise officials in December, drawing on

the Old Testament in reply to an officer batting for the workforce,

currently at four-fifths the sanctioned strength, to be enhanced.

The government has steadfastly denied it covets liquor revenues,

however, and the Excise Minister and other leaders have said on many

other occasions that the government cares more for people suffering

severe health problems because of consumption of spurious alcohol.

However, the Church and community-based organisations such as the

Young Mizo Association are not convinced. The modern-day avatar of the

traditional bachelor’s dormitory, the Young Mizo Association controlled

pre-colonial Mizo society by enforcing a code of honour, and continues

to have members in virtually every household.

Says Vanlalruata, general secretary of the Young Mizo Association,

“It is our stand that total prohibition should stay, and we have and

will continue to petition the government for it.”

Reverend Chuauthuama, one of the most vocal critics of the lifting of

prohibition, fears the effect of drink. “It’s something I have written

about many times, that as a society we are troubled by drink. Even in

historical writings we find that drunkenness led to violence and fights,

destroyed families and relationships and led to all kinds of social

evils. It will be no different now.”

Even the ruling Congress didn’t have it too easy. The Cabinet

tellingly backtracked once on discussing the new law before it was

finally introduced in the House. With the party enjoying total majority

in the Assembly, it was smooth sailing then on.

The opposition parties continue to object, and the Mizo National

Front has called a bandh on February 25. Apart from the rise in prices

of various government services, the protest is against lifting of

prohibition. “Total prohibition is in the best interest of the state’s

people,” says Leader of the Opposition Vanlalzawma.

Before the new Act was introduced, the Presbyterian Church’s top

authority, the Mizoram Synod, had put up posters with slogans such as

“It is more desirable to be poor without liquor revenue than to be rich

with it” and “Wine makes fools of us, alcohol leads to violence”.

More than 50 per cent of Mizoram’s population, including Minister Lalzirliana, are members of the Presbyterian Church.

The Young Mizo Association issued statements advising the government

to work towards strengthening prohibition, adding that it “wishes the

battle against alcohol and drugs continues”.

In Mizoram, the struggle against liquor has been at the forefront of

many an agitation. Volunteers from the Young Mizo Association and

neighbourhood watch bodies calling themselves Joint Action Committees,

and Village Defence Parties in villages, earlier carried out “checks”

and destroyed bootlegs. In the latter half of the last decade, such

vigilante action even claimed a few lives.

Police and excise officials continue to routinely arrest people for

any of several listed offences and promptly produce them in court.

This past Wednesday, seven young men stood in the courtroom within

the Aizawl District Court premises with their hands behind their backs

as green-bereted excise officers sat chatting on wooden benches just

outside.

As the judge read out each of the men’s names, they came forward and

murmured replies to the questions asked of them. As one young man in a

T-shirt, shorts and one missing sandal stepped up, an excise official

stared at him and asked, “Where did you leave your sandal?”

The other men snickered as the man scratched his head and grinned

sheepishly. The magistrate too chuckled under his breath as one of the

other accused men mumbled, “I don’t think he remembers.”

“Do you have money to pay the fine?” the judge asked.

The young man shook his head ambivalently.

“Well, you’ll have to sweep then,” the judge said, and wrote down the sentence.

He then called out the names of two other men who were presumably arrested together.

“What about you? You have money to pay the fine?” the judge asked.

“Yes sir,” said one confidently.

The judge gestured to the excise official and wrote down the sentence as the men were led out.

Outside, a group of young women giggled as the duo emerged and one of

them paid two Rs 1,000 notes to one of the seated excise officials.

As they all left, an official called after them, “Remember, you’re

paying the government for drinking.” It provoked another round of

laughs.

Inside, the judge finished sentencing the men.

Once all four of the men who were let off with a fine had left, the

officer who had collected the money turned to three young men sitting in

a corner.

“What happened to you? No money?”

The young men smiled embarrassedly.

“Well then, get ready to sweep. We have lots of places for you to sweep,” he said. The other officers laughed again.

As of today, in Aizawl district alone, 66 people have been arrested

for drinking without permits, of whom 47 have been sentenced to three

days each of community work, 14 let off with fines, and four others, who

failed to turn up for community service, sent to a month in jail.

One morning last month, as office-goers made their way to work, three

men in masks and caps earnestly went around cleaning up the milling

campus of the Aizawl Civil Hospital, much to the delight of the

administration.

One senior administrator looked at the men and asked the excise

official overseeing their sentences, “I thought there were five. Where

did two go?”

“They’re at the market. Cleaning up there,” the officer replied.

The administrator seemed pained the workforce had been split, but

said it was still a blessing since there was always a shortage of

sanitation staff at the hospital.

The men continued working, silently.

People queue up for application forms to get liquor cards at excise office in Aizawl.

People queue up for application forms to get liquor cards at excise office in Aizawl.