Two people die every three minutes in a country that accounts for 26 percent of cases globally.

By Bijoyeta Das

Diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) three years ago, Hasta - from Assam in India's northeast - has seen a doctor only four times. Samuel, 28, hired a wooden cart and took him to a public hospital in the town of Kokrajhar.

"I lose a day's work, wait for two hours, and the doctor meets the patient for only five minutes and never explains anything," he says. The doctor's visit was free, but X-ray and medicines cost $15 each time."

Rummaging under the bed, he pulls out

four crumpled prescriptions and two fading X-rays reports. The $3 he

earns as a day labourer feeds six people. Medicines for his father are

"simply not possible."

Scared that the disease could spread, he built a shed with bamboo, tin and tarpaulin for his father. "I want to take care of him. I just don't know how," he says, pressing his father's scrawny hands.

Many like Hasta are yet to benefit from the world's largest free healthcare programme for TB that India runs. India has the highest TB burden, accounting for 26 percent of cases globally.

It is the country's most fatal infectious disease and a rise in drug resistance has prompted many to ask if India is floundering to control TB.

India's TB burden

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2013 Global tuberculosis report, 8.6 million people developed TB and 1.3 million died from the disease in 2012. The rate of new cases has been declining at 2 percent per year for a decade.

The scale of India's TB control

measures is laudable but population, grinding poverty and a doddering

healthcare system cause the problem to dwarf all efforts, according to

experts. Prevalence has reduced from 465 to 230 per 100,000 population

and mortality from 38 to 22.

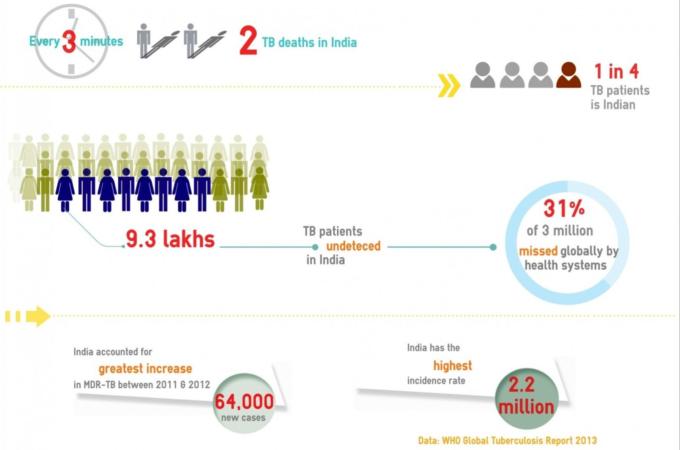

Yet, the scale of the scourge remains scary. Every three minutes, two people die of TB in India, and one out of every four TB patients in the world is an Indian.

"You are running very fast but you seem to be standing in the same place because so many are getting infected," says Virendar Chauhan, director of International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

For two decades, Indian government has been providing the WHO-recommended DOTS: Directly Observed Treatment courses under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). It currently reaches 1.5 million cases in the public sector.

But about half of those affected go to the private sector, which is not involved in TB control. "Government and private sector efforts should integrate. There should be a push-and-pull mechanism," adds Chauhan.

Routine DOTS saves lives but is not very effective in curbing transmission, says Madhukar Pai, associate director at McGill International TB Centre. "By the time patients end up in the DOTS system, they have likely infected many others."

Poor living conditions, malnutrition, overcrowding, smoking, indoor air pollution, HIV infection, and diabetes increase the risk of TB in India.

Pai says India's scale-up of new technologies has been disappointing. Countries such as South Africa and Brazil are actively investing in new tests such as GeneXpert to improve case detection and multi-drug resistant (MDR-TB) diagnosis, but India is yet to "take such bold steps."

"Even easily available tools like mobile phones and ICT are yet to be harnessed for notification and treatment adherence monitoring," he says.

According to Soumya Swaminathan, director of National Institute for research in Tuberculosis, poor access and ignorance about the national programme, unfriendly health services, and the attitude towards the marginalised are roadblocks in extending universal healthcare.

"Our studies have shown that there is a huge out-of-pocket expenditure by the time patients get diagnosed and treated for TB, and that stigma compounds the problem," she says.

The WHO says there is a funding shortfall of $2 billion a year for a full response to the global TB epidemic. But Indian health officials say India's TB control is a success and there are no funding gaps.

"India's TB spending has not slowed down and India's budget on TB control has increased by 300 percent in 12th Five Year Plan as compared to the 11th," says Niraj Kulshrestha, a senior official of the Central TB division at the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Spending on research increased by 80 percent since last year, he adds.

Fund shortage

International funds contribute 57 percent of India's total TB control budget. However, the RNTCP budget is only 2 percent of the total health sector budget. The ambitious National Strategic Plan that aims to treat 90 percent of TB cases by 2017 will cost $1.05 billion. But RNTCP has been allocated only $731 million.

Resistance to drugs is also compounding the problem. About half of the 450,000 MDR-TB patients are in India, China and Russia. Reports of recent drug stock-outs, particularly second-line MDR-TB, led activists of Treatment Action Group (TAG) to take over the stage with calls of "Shame India" and "the TB genocide must stop" at the 44th Union World Conference on Lung Health in Paris.

"It is a cruel irony that India is a pharmacy to the world. It produces many of the TB drugs that people in other countries depend upon," says Mike Fricke of TAG. "The government has not been upfront in recognising the shortage and ensuring availability."

Kulshrestha says there is no increase in MDR-TB and absolute numbers are high, proportionate to the population. "More cases are being reported because of diagnostic facilities made available by the government," he adds.

According to Leena Menghaney of Medicines Sans Frontiere,"Antibiotics are largely misused in the private sector, which is contributing to the rise of drug resistance in TB and needs to be regulated."

Often poverty makes people susceptible to TB, and TB worsens poverty, but it now affects all classes of people in India.

“If India and China are able to reduce the TB burden, it would mean progress for global TB control,” she adds.

This story has been written under the aegis of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union)'s Media Fellowships for Reporting on TB.

By Bijoyeta Das

Rafael Hasta, 58, has yet to benefit from the world's largest free TB care programme [Bijoyeta Das/Al Jazeera]

The days Rafael Hasta

coughs up blood, his son Samuel gives him mashed papaya with boiled rice

and red tea. Hasta refuses to eat anything else.Diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) three years ago, Hasta - from Assam in India's northeast - has seen a doctor only four times. Samuel, 28, hired a wooden cart and took him to a public hospital in the town of Kokrajhar.

"I lose a day's work, wait for two hours, and the doctor meets the patient for only five minutes and never explains anything," he says. The doctor's visit was free, but X-ray and medicines cost $15 each time."

Scared that the disease could spread, he built a shed with bamboo, tin and tarpaulin for his father. "I want to take care of him. I just don't know how," he says, pressing his father's scrawny hands.

Many like Hasta are yet to benefit from the world's largest free healthcare programme for TB that India runs. India has the highest TB burden, accounting for 26 percent of cases globally.

It is the country's most fatal infectious disease and a rise in drug resistance has prompted many to ask if India is floundering to control TB.

India's TB burden

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2013 Global tuberculosis report, 8.6 million people developed TB and 1.3 million died from the disease in 2012. The rate of new cases has been declining at 2 percent per year for a decade.

|

| Earning $3 per day, Samuel says its "simply impossible" to buy medicines for his father [Bijoyeta Das /Al Jazeera] |

Yet, the scale of the scourge remains scary. Every three minutes, two people die of TB in India, and one out of every four TB patients in the world is an Indian.

"You are running very fast but you seem to be standing in the same place because so many are getting infected," says Virendar Chauhan, director of International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

For two decades, Indian government has been providing the WHO-recommended DOTS: Directly Observed Treatment courses under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). It currently reaches 1.5 million cases in the public sector.

But about half of those affected go to the private sector, which is not involved in TB control. "Government and private sector efforts should integrate. There should be a push-and-pull mechanism," adds Chauhan.

| It is a cruel irony that India is a pharmacy to the world. It

produces many of the TB drugs that people in other countries depend upon

... The government has not been upfront in recognising the shortage and

ensuring availability. |

Poor living conditions, malnutrition, overcrowding, smoking, indoor air pollution, HIV infection, and diabetes increase the risk of TB in India.

Pai says India's scale-up of new technologies has been disappointing. Countries such as South Africa and Brazil are actively investing in new tests such as GeneXpert to improve case detection and multi-drug resistant (MDR-TB) diagnosis, but India is yet to "take such bold steps."

"Even easily available tools like mobile phones and ICT are yet to be harnessed for notification and treatment adherence monitoring," he says.

According to Soumya Swaminathan, director of National Institute for research in Tuberculosis, poor access and ignorance about the national programme, unfriendly health services, and the attitude towards the marginalised are roadblocks in extending universal healthcare.

"Our studies have shown that there is a huge out-of-pocket expenditure by the time patients get diagnosed and treated for TB, and that stigma compounds the problem," she says.

The WHO says there is a funding shortfall of $2 billion a year for a full response to the global TB epidemic. But Indian health officials say India's TB control is a success and there are no funding gaps.

"India's TB spending has not slowed down and India's budget on TB control has increased by 300 percent in 12th Five Year Plan as compared to the 11th," says Niraj Kulshrestha, a senior official of the Central TB division at the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Spending on research increased by 80 percent since last year, he adds.

Fund shortage

International funds contribute 57 percent of India's total TB control budget. However, the RNTCP budget is only 2 percent of the total health sector budget. The ambitious National Strategic Plan that aims to treat 90 percent of TB cases by 2017 will cost $1.05 billion. But RNTCP has been allocated only $731 million.

Resistance to drugs is also compounding the problem. About half of the 450,000 MDR-TB patients are in India, China and Russia. Reports of recent drug stock-outs, particularly second-line MDR-TB, led activists of Treatment Action Group (TAG) to take over the stage with calls of "Shame India" and "the TB genocide must stop" at the 44th Union World Conference on Lung Health in Paris.

"It is a cruel irony that India is a pharmacy to the world. It produces many of the TB drugs that people in other countries depend upon," says Mike Fricke of TAG. "The government has not been upfront in recognising the shortage and ensuring availability."

Kulshrestha says there is no increase in MDR-TB and absolute numbers are high, proportionate to the population. "More cases are being reported because of diagnostic facilities made available by the government," he adds.

According to Leena Menghaney of Medicines Sans Frontiere,"Antibiotics are largely misused in the private sector, which is contributing to the rise of drug resistance in TB and needs to be regulated."

Often poverty makes people susceptible to TB, and TB worsens poverty, but it now affects all classes of people in India.

“If India and China are able to reduce the TB burden, it would mean progress for global TB control,” she adds.

|

| TB-Infographic [Bijoyeta Das /Al Jazeera] |

This story has been written under the aegis of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union)'s Media Fellowships for Reporting on TB.

The CM with a tilak on his forehead

The CM with a tilak on his forehead